|

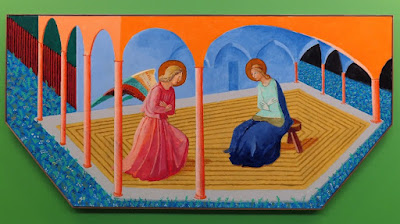

Cristoforo Allori, Judith and the head of Holofernes, Royal Collection: 'her hair fell in a wave like that of Allori's Judith in the Palazzo Pitti'.

|

This is not a review of Turgenev's Spring Torrents (1872) by a literary critic; this is written by

a reader who has just completed the novel.

I am not unfamiliar with Turgenev; I remembered his lovely Notes

from a Hunter’s Album for his comprehension of the serfs, which struck me

as very unusual for his time. I had read about his long-term liaison with a

famous opera singer, but I did not know the details.

So I began Spring Torrents and was captured by its seeming

simplicity. I read the book with interest (to see what would happened, then bewilderment

(as the book seemed to be a standard work of romantic fiction, worthy of Mills

and Boon), followed by fascination as the story moved on.

This short novel, just 163 pages in the Penguin translation

by Leonard Schapiro, can conveniently be divided in two parts. In part one, the

hero, Sanin, who is Russian, and aged 23, is travelling back from several

months in Italy to Russia via Germany. He has a small private income, but he

has exhausted his funds. He encounters a poor family who run a patisserie, and

within hours, Sanin finds himself involved in a duel to defend what he perceives

to be a slur on the daughter’s honour. No sooner is that trial over than he has

declared his love for Gemma, the daughter and she accepts him She abandons her

fiance for him, and everything seems set for them to lead a quiet and contented

life of small-scale bourgeois respectability together.

In the second part, linked only very tenuously to the first,

he travels to Frankfurt to sell his estate. But the woman who has the money to

buy his estate, Maria Nicolaevna, turns out to be interested in considerably more

than a simple business deal. He is swept off his feet by her forthright views

and invitation to intimacy, and abandons his fiance to travel with Maria to

Paris, despite the fact that she is still living with her husband (it appears

she simply married him for convenience).

The whole tale is framed by the author looking back 30 years

after these events took place, remembering with regret how he fell for Maria Nicolaevna,

and how she soon abandoned him. We learn that he never married, and as a kind

of epilogue to the novel, he discovers his former betrothed, Gemma, is happily

married with five children.

There are, of course, various ways in which a reader can interpret

this tale. The translator, Leonard Schapiro, sees it in biographical terms,

since Turgenev spent many years as the lover of Pauline Viardot, a famous opera

singer, despite her being married to someone else. But as I know little of

Turgenev’s life, let’s leave this interpretation to one side. Another

interpretation is, of course, what might be expected to be the mainstream

19th-century view: a romantic liaison with a woman based simply on passion is

frowned on. By this view, it is clear which of the two liaisons should be

preferred by the reader.

We have here a contrast between two women, seen from a man’s

point of view. One, Gemma, is innocent, young, unworldly, and would appear to

have little in common with Sanin, the hero, who is clearly well travelled and,

one would assume, widely experienced, although still young, at 22. For me, the

crucial pointn is that the tale shows hardly anything about Gemma’s character.

We learn a lot about her beauty, but of her mind, her views, we learn next to

nothing. Is there any evidence in this novel that Sanin knows her, or she him,

in any detail? I don’t think so.

The other woman, Maria Nicolaevna, is a whirlwind, a force

to be reckoned with. She treats her husband with contempt, calling him “fatty”,

and is similarly abrupt with other former lovers. She has a very clearly stated

view of life: “Cela ne tire pas a consequence”. She succeeds in seducing

Sanin, and her triumph wins her a bet she has with her husband – he is clearly

reconciled to his very subordinate position in her life.

What makes the novel fascinating is the character of Maria

Nicolaevna, the strong-willed and assertive woman who demands openly what she

wants, and, it would appear, usually gets it. Sanin appears to acknowledge he is

not in love with her, but after a few hours in bed with her, abandons his future

marriage and follows her obediently to Paris.

How should we interpret this seemingly simple novel? Sanin, reflecting

on these events many years later, and looking back as his young self, condemns

Maria Nicolaevna, or at least condemns himself for getting carried away. But could

he ever have been happy with Gemma? He knew nothing about her; it was an

invented, one-sided relationship, he and an artificial image he had of her.

By comparison, the novel comes to live in the description of

Maria Nicolaevna and her fiery, haughty attitude to life. This is a novel that

ranks very highly for eroticism (which is considerably rarer than you might

imagine in the novel): the scene in the opera house where Maria Nicolaevna more

or less seduces Sanin is adult in a way that Dickens, for example, could never

achieve. Here is a real character, aware of and celebrating her passion, and

unafraid to treat with contempt those who, she feels, do not stand up to her.

However impossible it might be to live with such a woman, the depiction by

Turgenev of this character was for me totally unexpected after the rather

comfortable and small-scale bourgeois love affair in the first part. The novel

began with a typical 19th-century novel plot: man falls for a woman about whom

he knows nothing, and invests her image (largely because he knows so her so

little) with such significance he is prepared to die in a duel for her. Sweet,

but pointless. Compare this with his few nights of pleasure with a woman of

character, of experience, who knows exactly what she wants and is not afraid to

ask for it.

The Allori picture as it appears in the Penguin edition |

Footnote: Even today, in the 21st century, we are frightened by female desire. It was fascinating to notice that Sanin, in his first description of Gemma, compared her to Judith, in the depiction shown above. However, the Penguin image carefully omits the head of Holofernes; all you see is a powerful female face in half profile. Perhaps the full image might have been too off-putting for the average reader.