|

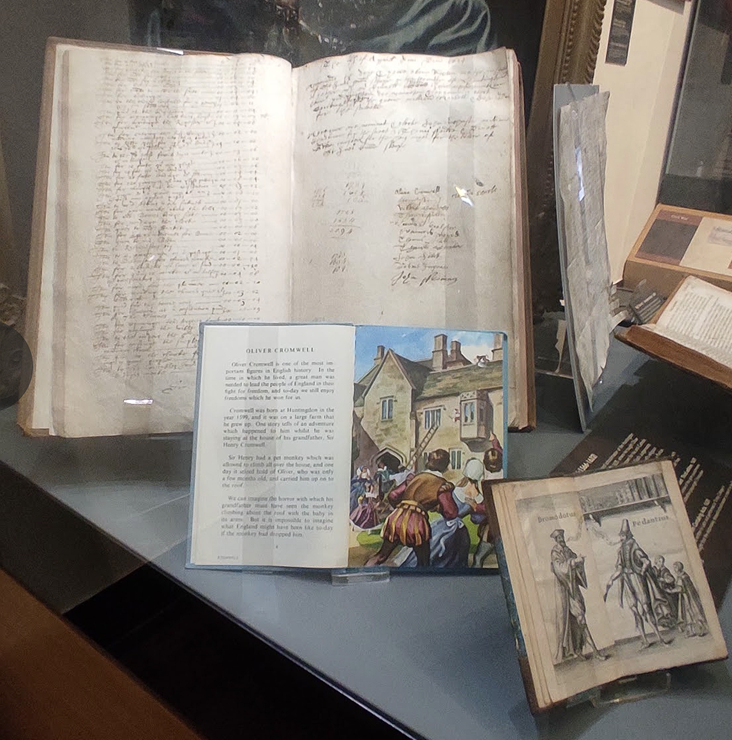

Not many museums include the Ladybird book on the subject

alongside primary sources

This museum was a revelation: a great topic, fascinating and informative displays, interested and chatty staff, and the museum packed with visitors. I’ve been to many small museums in the past few years, and they are usually silent, well-meaning, but out of date. This one is a glorious exception.

You would think that Cromwell is a sufficiently interesting

topic, controversial even today, for any museum, but a contrast with the

Cromwell House in Ely is very revealing. The Cromwell House is kitted out as a 17th-century domestic house, but contains nothing of relevance to Cromwell himself. As the staff in Huntingdon described

it, they’ve got the building, but we’ve got the stuff. And so they do! Just one

room, but packed full of items belonging to, written by, or associated with

Oliver Cromwell. And not just meaningless memorabilia, for the most part. Each of the bays shows a different part of

Cromwell’s life, with the first bay showing a Ladybird book from 1963 about Cromwell,

and the final bay showing his influence, including a model of the British Railways

steam engine, the Oliver Cromwell, built 1951 (at which time it was clearly

acceptable to name an engine after this controversial figure) and the title

page of Carlyle’s Speeches of Oliver Cromwell’s Letters and Speeches (1845).

Like many major figures, Oliver Cromwell means different things to different generations. I was fascinated not only by the way public opinion seems to have shifted from revulsion (after his death in the 17th century) to rehabilitation (from Carlyle and others) leading to his statue being placed in Parliament Square, where it remains today. For much of the 20th century he was a hero, if the Ladybird book (by I du Garde Peach, 1963) is anything to go by. The Ladybird book, ostensibly for children, begins:

Oliver Cromwell was one of the most important figures in English history. In the time in which he lived, a great man was needed to lead the people of England in their fight for freedom and to-day we still enjoy freedoms which we won for us. [p4]

As for parallels with other despots, Cromwell appears

to be more on a par with Lenin than with Putin, in that he at least started from a principled and justifiable position, even if he could not justify all his actions, whereas typical dictators act from self-preservation and appealing to the worst instincts of the populace.

Valiantly, the museum attempted to cover the historiography as well as the objects (paintings, hats, letters). In addition, the museum included a timeline of Cromwell’s life and contemporary affairs, several information boards, question-and-answer panels (“Did Cromwell abolish Christmas?”), together with the usual dressing-up items of armour and clothing for children, plus Cromwell tea towels and fridge magnets, and even ended with an illuminated quiz so you could compare your view of Cromwell before and after visiting the exhibition.

Finally, as if that wasn’t enough, the museum had free admission

(compared to £6.50 for standard admission to the Cromwell House in Ely), and stated

it receives no government support. It sets a standard for other museums to try

to match. There will never be agreement about a figure as divisive as Cromwell,

but that’s no bad thing. On leaving the museum, there were campaigners in the

market calling for an end to immigration and to “ideological teaching” in

schools. I can’t help feeling that a museum like the Cromwell Museum generates reasoned

discussion rather than mindless ranting. When I got home and showed my Cromwell

quotations tea towel there was general derision in the household; but you don’t

have to agree with everything he said to take him seriously.